“Steel String Americana” CD

Such a Night

Mac Rebennack (aka Dr. John), is a fairly imposing piano player. In his playing, you can hear the long and diverse history of the New Orleans bar-room piano tradition, distilled down to a personal essence that is unmistakeable. I especially love the infrequent moments when Mac plays by himself. To me, it’s then that his “roots are showing” a little more clearly– when he’s forced to make all the music himself, as his forebears did.

Happy Thumb

Happy Thumb

Blind Blake was certainly one of the greatest out-and-out guitar virtuosos this country has ever seen. He was first recorded in 1926, and quickly became one of country blues’s hugest sellers. He inked the blueprint for the styles of Rev. Gary Davis, Josh White, Bill Broonzy, Jorma Kaukonen, and many others that followed- but all agree that his speed, touch, feel, and originality have never been equaled.

What I find so attractive and uniquely dazzling about his playing is his stride piano concept- Gary Davis called it his “sportin’ right hand”. The title of this homage to Blake’s playing was a phrase some marketing wag at Paramount Records came up with to sell his style to the public.

You Can’t Get That Stuff No More

This distinctly pre-internet paean from 1932 was one of many churned out by guitarist Tampa Red and pianist Georgia Tom. These guys started the “hokum” craze with the bawdy party tune “It’s Tight Like That”, and rode it for many years.

This distinctly pre-internet paean from 1932 was one of many churned out by guitarist Tampa Red and pianist Georgia Tom. These guys started the “hokum” craze with the bawdy party tune “It’s Tight Like That”, and rode it for many years.

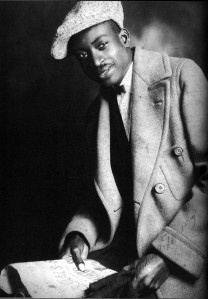

As huge a hit as hokum was, Georgia Tom made his indelible mark on American music somewhat later. After his wife died during childbirth in a Chicago hospital while he was playing on the road, he abandoned the nom de stage, and turned single-mindedly to writing songs which combined his bluesy musical sensibility and crowd-pleasing instincts with Christian themes. He called it “sacred blues”, but the  term quickly given to Thomas Dorsey’s musical vision was “gospel music”.

term quickly given to Thomas Dorsey’s musical vision was “gospel music”.

From our vantage point in the 21st century, it’s not overreaching to claim that the synergy of forces in the music Dorsey created has become the single most influential force in American popular culture, giving birth to rock and roll, R&B, Motown, and putting the concept of “soul” on the map.

It’ll be a sad day when “you can’t get THAT stuff no more”!

Down In the Valley to Pray/Jesus, Make Up My Dyin’ Bed

Two spirituals from the incredibly rich musical traditions of the American South. One is tempted to say that the first is Appalachian, meaning that its roots are in the British Isles, while the second is African-American. My interpretation of these tunes certainly may seem to argue that case- but the itinerary of Southern folk traditions continually confound this narrow logic. Listen to Leadbelly sing “Down in the Valley to Pray” on the Lomax Library of Congress recordings for a taste of what I mean!

Two spirituals from the incredibly rich musical traditions of the American South. One is tempted to say that the first is Appalachian, meaning that its roots are in the British Isles, while the second is African-American. My interpretation of these tunes certainly may seem to argue that case- but the itinerary of Southern folk traditions continually confound this narrow logic. Listen to Leadbelly sing “Down in the Valley to Pray” on the Lomax Library of Congress recordings for a taste of what I mean!

Conversely, listen to Led Zep’s version of “In My Time of Dying” to see how this spiritual made the reverse trip across the Atlantic.

I play these tunes in DADGAD tuning.

My Blue Hellhound

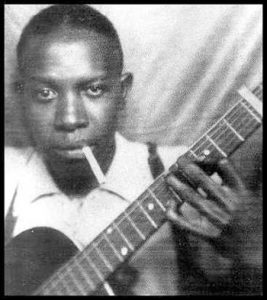

I came of musical age living on Chicago’s South Side. A few blocks away from me lived Johnny Shines, a bluesman who had played and run with Robert Johnson. During one of my visits, Johnny marveled aloud at how Robert would “hear a tune once on the radio”, and be able to play the song perfectly at the gig that night. Johnny maintained that this was true for standards of the day, as well as the blues tunes we now associate with him; one of his most-requested tunes, Johnny said, was a song recorded in 1927 by crooner Eddie Cantor called “My Blue Heaven”.

What would I not give for the opportunity to hear what Robert Johnson would have done with that tune, or “Tumblin’ Tumbleweeds”, or other tunes that Johnny insisted flowed out of him at their nightly gigs? Can you imagine what that might have sounded like?

I did.

Stardust

Hoagy Carmichael wrote this tune in 1927, and the first of many hit versions was recorded in 1930.

Hoagy Carmichael wrote this tune in 1927, and the first of many hit versions was recorded in 1930.

Songs like “Stardust” represent a different warp in the fabric of American music. Written by professional songwriters and played by bands distinguished more by horns than stringed instruments, they have come to be known as “standards” in the jazz world, in much the same way that “Sweet Home Chicago” is for the blues world.

I’ve tried to recast this seminal jazz tune into the modern world of steel-string sonics, much as Eddie Lang did in the ’30’s, Django Reinhardt in the ’40’s, and George Barnes in the ’50’s. Mike Sucher joins me on Hammond B-3.

Transposing it from Db to A helps!

Stack-A-Lee

Stack-O-Lee, Stagolee, Staggerlee… there are as many musical variants of this folk epic as there are spellings of the man’s name. And i mean entirely different SONGS here, with different melodies, refrains- practically everything different except the mythical bad dude with the original bad ‘tude.

Stack-O-Lee, Stagolee, Staggerlee… there are as many musical variants of this folk epic as there are spellings of the man’s name. And i mean entirely different SONGS here, with different melodies, refrains- practically everything different except the mythical bad dude with the original bad ‘tude.

Don’t ask how many VERSIONS there are- the last figure I saw was 187, including artists ranging from Mississippi John Hurt to Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians, from Dr. Hook to Dr. John.

Like all legends, urban or otherwise, the story of Stagolee seems to have begun with an actual event. A 1895 news article in St. Louis’ Globe-Democrat tells the sordid tale of a shootout between one William Lyons and a fellow named Lee Sheldon. The article notes that Sheldon “is also known as ‘Stag’ Lee”. Musical tellings of the tale seem to have begun shortly thereafter.

A New Orleans blues piano player named “Archibald” recorded a version in 1950 that put the story to a much more urban style. 55 years after the event that inspired the legend, this version briefly became a Top Ten R & B hit; then Lloyd Price remade his version in 1959, and put the song on the pop music map forever.

The Louisiana variant of this tune seems to represent a different branch of the Stagolee tree than the Furry Lewis/John Hurt songster variant. My version comes more from the Louisiana side of the family.

Amos Moses

Anyone who’s checked out Jerry Reed’s incredibly funky fingerpickin’ knows there’s a lot more to this guy than “Smokey and the Bandit”! Ever wonder what rockabilly guitar would sound like played on a nylon-string guitar? Listen to “The Claw” for an idea of where Merle Travis’ style wandered off to….

This song was a hit for Jerry in 1970- and, more recently, Les Claypool of Primus covered it, explaining that it was the first 45 he had ever bought.

Bury Me Beneath the Willow/Redwing/Knuckle Breakdown

I think the first time I heard Doc Watson was on a 1963 double-bill in NYC with Mississippi John Hurt. To this day, I can’t picture a more appropriate pairing to illustrate the wonderful “mongrelization” of Southern musical tradition!

I think the first time I heard Doc Watson was on a 1963 double-bill in NYC with Mississippi John Hurt. To this day, I can’t picture a more appropriate pairing to illustrate the wonderful “mongrelization” of Southern musical tradition!

Doc, of course, opened the door for a generation of extraordinary flat-picking guitarists, but none has surpassed Doc in the 3 T’s of taste, tone, and timing. I’ve put together a medley of 2 familiar (and 1 not-so-familiar) tunes, that sounds to me like something he’d do.

The first tune is an old Carter Family classic, recorded in the late 20’s, and presumably much older than that. I recall first hearing it on one of my dad’s 78’s.

The second tune appears in the repertoire of many fiddling traditions- but I first heard it as the melody of “There Once Was a Union Maid”, a Woody Guthrie anthem that was very much part of the ambient soundtrack of my family’s house while I was growing up.

The last tune is something I threw together as a “finger-buster” many years ago. I’d like to thank my friend Jim McGinniss for alerting me to the possibility of redemptive musical value in it!

I Loves You, Porgy

I first heard Nina Simone’s version as an impressionable teen while poring through my Dad’s record collection.

I first heard Nina Simone’s version as an impressionable teen while poring through my Dad’s record collection.

George Gershwin’s 1937 masterpiece “Porgy and Bess” is a paradigm for what I’ve tried to do with the “roots music” inspirations I’ve always had, and the wider musical vocabulary I’ve tried to acquire over the years. In Gershwin’s landmark opera, the mood, melodies, and ornamentations of the blues are combined with a capacious harmonic palette to create an emotional experience that is, in Duke Ellington’s phrase, “beyond category”.

I first conceived of this as a guitar solo, before enlisting the vocal talents of a dear friend, Miss Sandra Wright.

You’ve Been a Good Ole Wagon

I first heard this song from Dave Van Ronk, whose playing was a revelation for me early on. His recent sad passing reminds me of his immense influence and contribution to “steel-string americana”.

The tune was originally recorded by Bessie Smith (with Louis Armstrong on trumpet) in 1925, when “The Empress of the Blues” enjoyed a position unrivaled by any blues artist, male or female. It’s astonishing to think of the flamboyantly dominatrix persona that Bessie rode to stardom- this only a couple of years after woman were first allowed to vote!

Anyone foolhardy enough to attempt this incredibly gender-specific song runs the risk of being called a “musical cross-dresser”, I suppose… but it’s such a great tune, I decided it was worth the risk!

Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?

This Carole King tune became classic americana when the Shirelles’ rendition hit the airwaves in 1961. What entertainment biz professional hasn’t asked this existential question?

This Carole King tune became classic americana when the Shirelles’ rendition hit the airwaves in 1961. What entertainment biz professional hasn’t asked this existential question?

I’m joined here by my long-time bassist bandmate, Tony “The Meat Man” Markellis.