Scribblins

“Music expresses that which cannot be said, and on which it is impossible to be silent.” Victor Hugo

Around 30 years ago, before the ubiquity of desktop publishing, blogging, and the interwebs, I produced a newsletter for the group I played most regularly with… The Unknown Blues Band. The job began as a necessary chore– informing our regional fans about upcoming dates, recordings, and band news– but eventually morphed into a creative outlet. I was surprised to find that I could derive almost as much satisfaction from constructing a phrase using words as I did playing ones made from notes. The need for a newsletter ended decades ago, but my appreciation for the well-turned phrase never did.

From time to time, I’ve put virtual pen to virtual paper, in hopes of expressing some of the things that words CAN say. And, occasionally, some things on which it was impossible to be silent. Here are some of them… ![]()

My ‘55 Tele

In 1968, when I was 19, I was living on the South Side of Chicago, doing freelance gigs in blues bars with musicians who had been my personal heroes several years earlier. I was using a Supro guitar then… a budget brand which would later become iconic (and valuable) due to its association with players like Jimmy Page, Jack White, etc.

One night, I walked into the bedroom of my apartment, just in time to see the case disappear out my open window; a guy had used a board to shimmy over from the back porch of a neighboring building, reached in, grabbed the guitar, and was racing down the stairs with it as I watched helplessly from my now-guitar-less room.

I had no money, but I needed to get another guitar for my upcoming gigs. The Martin 00-18 that my dad had bought me as a birthday present 5 years earlier was the only liquid asset I had… so when a friend offered me $100 for it, I took his offer.

In a pawn shop several blocks away, I found a Fender Telecaster– a quintessentially workingman’s guitar, with the wear of countless gigs already on it. The well-worn maple fingerboard and discolored white pickguard told me that this Tele was built at least 10 years earlier. I was intrigued by the stories that Tele could tell…. if only the scratches, cigarette burns, and worn paint–where the previous owner’s right arm had rested–could have talked!

But most of all, I was intrigued by the price… $75. A workingman’s guitar, at a workingman’s price. I bought it, and showed it to a friend, who told me that the low serial number on the neckplate indicated that it was built in 1955… only a few years after the revolutionary solidbody design was first introduced.

Those details, however, were of no concern to me. I saw the guitar as a tool for playing the music I loved… and nothing more.

Nevertheless, I soon discovered that the tone and feel of this Tele inspired me, in a way that the Supro–or even my Martin–never had. By this time, I was playing 4-6 nights/week, in blues clubs and studios all over the city. The Tele quickly became a full-fledged partner for me, and playing it created so much joy for the music… so that even the dullest of tunes, on the dreariest of gigs, became fun. I didn’t know what true communion with one’s instrument was, until that guitar came along.

By 1971, I had had my fill of smoky bars, city streets, and getting to bed at 5AM. I longed for a simpler, quieter life. My then-girlfriend and I moved to North Duxbury, Vermont, and built a geodesic dome. I suppose I assumed I would be trading my music career in for a job in some sawmill somewhere. Imagine my surprise, when I soon discovered that my most marketable skill in this rural backwater was playing electric guitar!

Fortunately, I still had my trusty ‘55 Tele– and it soon saw as much use in my new rural home as it ever did in Chicago.

By the mid-70’s, it was apparent to most guitarists that the 3 elite manufacturers–Martin, Gibson, and Fender–were consistently making instruments far inferior to what they had built 20–or even 10–years before. By now, people were noticing the distinctive look of my ‘50’s-era Tele at gigs, and viewed the “mojo” of its wear marks as a badge of distinction; battle scars which spoke not of careless overuse, but rather, of honorable service in the line of duty. The word “vintage” was now being applied to guitars… and my ‘55 Tele clearly was the quintessential vintage guitar.

Somewhere in those mid-70’s, however, I stopped being as inspired by the Tele as I once had been. Was it the fact that I was playing more bebop-style jazz… a music that is customarily played on larger hollowbodies? Or maybe it was that last neck re-fret, which seemingly had made the Tele play worse than it had previously? I don’t know. All I knew was that other instruments seemed now to possess a better voice for the music I was now aspiring to play.

In guitarist circles, a common meme is that you can only have one wife… but you can have many guitars. As moods and musical preferences change, you can pull a different guitar from the closet… as long as your closet is big enough. But by 1989, the Tele had occupied a spot at the back of the closet for almost 10 years. So, when I needed a larger-than-anticipated down payment to buy my first house, I started to think about selling the Tele.

A guitar student friend had made a standing offer of $800 for the guitar. $800? That was over 10 times what I had paid for it, and seemed like an offer that I should jump on immediately, before he came to his senses, or before the “vintage bubble” burst! Any nostalgia I had was overridden by the need for cash… so the deal was done, and the house was bought.

End of story? Not quite.

As anyone who knows vintage guitars will tell you… that ‘55 Tele is now worth between 10-$15,000, and will undoubtedly continue to rise in value. As if that wasn’t enough– every few months, I hear from someone who sees the Tele on my buddy Jim Weider’s iconic Fender video, where he analyzes the guitar in depth, plays it, and points out the spot where I signed the guitar on the back (at my friend’s insistence). The last I heard, the guitar belongs to a collector in Norway.

Maybe it’s true, what they say. If you love something, set it free.

![]()

My First Record

My first record was a 45RPM single that i bought when I was 9 years old.

I grew up in inner-city Chicago, and my family was taking a trip to Arkansas, so that my dad could interview a songwriter named Jimmy Driftwood, for a magazine article. While my dad and mom were staying at the Driftwood’s cabin in Timbo, I was placed in a horse camp in the nearby town of Mountain View, where I was freaked out by campfire stories of water moccasins, and by the prospect of using the smelly, communal outhouse for a week. (I learned that you can’t go for 2 weeks without making #2… but that’s another story for another time.)

Anyway, in my occasional trips to town, I heard a song on the jukebox of a local cafe that my friends and I were not supposed to go into. The tune sounded fantastic. Its name was easy to remember, because the refrain repeated constantly… “Alley Oop… Oop.. Oop-Oop”. I had heard vibey, “street-sounding” music like it back home in Chicago… but this tune had a Flintstones-cartoon aspect that made it even better.

I had saved enough allowances to buy the 45.. but didn’t know how one went about doing that. My friends at the horse camp directed me to a local hardware store– which was where one bought records in Mountain View, Arkansas– and I bought my first-ever record.

When I brought the 45 home and played it, I had the first in a lifetime of subtle letdowns; the experiencing of listening to my own record was not as thrilling as listening to it on the jukebox in the cafe. A profound realization, and the first in a lifetime of similar epiphanies- but I found out later that there was a more mundane explanation. The original version I heard in the cafe was by a hastily thrown together doo-wop group from Los Angeles that called themselves the Hollywood Argyles. But the copy that I had bought at the hardware store was by a “cover group” called Dante and the Evergreens. The song, the arrangement, and the goofiness were the same, but the vibe was less edgy, more antiseptic– as the producers no doubt intended, to appeal better to young white audiences.

But the “bait n’ switch” tactic didn’t work for me. I was indignant, when I realized how it all worked… and have spent the better part of a musical lifetime trying not to confuse the “cover” with the “real deal”!![]()

Reminiscences of Doc

By the age of 15, I had already assembled a personal pantheon of guitar heroes. At the tippy-top of that heap were Lightnin’ Hopkins, Dave Van Ronk, and Mississippi John Hurt. So, imagine my delight when I caught wind of a show in New York City, in November, 1964, with all three of them. True, it was at Carnegie Hall- not exactly the place one would expect to see a blues show. But still, the opportunity seemed too good to pass up… especially since I had only HEARD Lightnin’ Hopkins on records, at that point.

There was another guy on the bill, who I’d only heard of by reputation. He was a country guitarist, by the name of Doc Watson. (Being an avid Sherlock Holmes fan, the name was already intriguing!) I was puzzled by why a country guitarist would appear on the same bill with three blues guitarists… a recollection that now allows me to chuckle at how much a 15-year-old still has to learn.

Anyway, this Watson guy was everything I had imagined him to be, and THEN some. A BIG some. In fact, the amazing renditions of old mountain tunes, gospel hymns, finger style blues, and flat out bluegrass barnburners, performed by just one guy on guitar, was a huge eye-opener for me. For starters, the guy seemed to display an incredible ease, while hitting technical benchmarks which I hadn’t known even existed yet. But even more baffling to my youthful perspective was the authority with which this guy performed the entire panorama of American folk music, without ever once appearing false or strained. That ease and authority is a goal which I have striven for in my own playing ever since.

The next spring, my dad was hired to do a magazine article about a guy named Billy Barnes, who worked in Asheville, North Carolina, for one of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty programs. My dad asked if I’d like to come along on the trip. On the way down, my dad started dangling hints about a little detour he wanted to take. We turned off the main highway, and as we went farther, the road got rougher and windier, and eventually turned to dirt. At just about the point when I started thinking “Where the hell are we going?”, my Dad pointed to a sign, and said “See what that sign says?”. I read the sign aloud, which said “Welcome to Deep Gap”. I said excitedly, “Deep Gap? Dad! Deep Gap is where Doc Watson lives!” My dad said “It sure is. And we’re going to drive up to Doc’s house, and get him to sign your album!” I still treasure that original album, with the moody muted-gray photo on the front, to this day.

Fast forward to 1992, when my now-wife and I were driving down to New Orleans, for her first taste of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. We had more time on our hands back then, so we decided to take slow, ”scenic” routes, as opposed to the interstates. While meandering through the back roads of North Carolina, I decided to repeat my dad’s mischievous prank. Despite the 27 years, which seemed to have brought some improvement in the road surfaces, the sign reading “Welcome to Deep Gap” was still there.

Now, Celia had served as Box Office Manager for the Flynn Theater for 15 years, so she knew Doc as a performer who consistently sold out the 1500 seat venue every year or so. I think it’s safe to say that Celia was as big a fan of Doc as I was… and for many of the same reasons. Nevertheless, it was with some amusement that she saw the unprepossessing small town that Deep Gap still was in 1992.

On the way out of town, I happened to notice a diner on the left-hand side, with the Blue Plate Special spelled out using those marquee letters one finds throughout the south… whether in front of diners, theaters or churches. Underneath the lines of type touting the meatloaf, cottage cheese, and wax beans was the words, “Appearing Saturday”. Underneath that was the letter “D”, then a space, and then the letter “C”. Underneath that, irregularly spaced, were the letters “W”, “T”, “O”, and “N”. I immediately hit the brakes, and started to turn around. Celia said in a surprised voice, “WHAT are you doing?” I said “Didn’t you see that sign?” She said “You mean… about the Blue Plate Special?” I said “No. Right underNEATH that”, and pointed at the sign, which was now directly in front of our car. She saw the same thing I saw- but apparently wasn’t reading it as I was reading it- because when I said “Don’t you see? It says Doc Watson”, she said “That’s ridiculous. First off, it’s missing most of the letters. And second off, why in the world would Doc Watson be playing at this tiny diner?” Undeterred by the undeniable logic of her points, I said “I’m going to go in and ask”.

Since by now it was well past lunchtime, there were only a few regulars still sitting at the counter. I had to wait a bit before I could get the attention of the waitress, who obviously had better things to do then to wait on the stranger who had just walked in. Upon capturing her indifferent attention, I said “Sorry to bother you, ma’am… but could you tell me what the sign outside says, underneath the Blue Plate Special?” Her vacant look made it clear that she had no idea what I was talking about, or much interest in finding out. I decided to take the plunge into the water of my harebrained theory, and asked “Is there someone who plays here on Saturday nights?”

Without any change in her bored expression, she said “Oh honey, there’s just some fella who’s a friend of the owner, who plays here sometime.” Seeing my expression of interest, she pointed to a far corner of the room, where there were some boxes of canned goods and soda, and said “Yeah, he sets up over there and sings and plays the git-tar”. I said “Is his name Doc Watson?” As an expression somewhere between irritated and amused flickered across her face, she turned to the kitchen and yelled “Hey, Sam! What’s the name of that boy that plays in the corner on Saturday night? You know… Fred’s friend, that plays the git-tar?”

Sam yelled back something that was apparently as incomprehensible to her as it was to me. She looked at me with an expression that contained a bit more irritation, and a bit less amusement then earlier, and said “What did you say his name was again?” I said “Doc. Doc Watson”. She turned again to the kitchen and yelled “Is his name Watson, or something like that?” This time, Sam’s reply was a bit clearer. “Yeah. That sounds about right.”

So, there you have it. A man can travel across the globe- touching literally millions of people with his charmingly unadorned personality, setting impossibly high standards for those guitarists unfortunate enough to follow in his wake, and inspiring thousands of musicians to think a bit broader about how to play and present their music- and still be a stranger in his own small town. Life’s funny that way.

Fast forward again, to 2012. I was in Italy with my wife, at a festival dedicated to American “Roots Music”- a term that would’ve puzzled Doc, no doubt, but a category which he is as responsible for as anyone in the history of American music. I was sitting on the balcony of our pensione, catching a bit of Wi-Fi from the café across the street, when I read the news that Doc had passed. Writing this, years later, I still get choked up by the memory, and of American music’s collective loss.

Happy birthday, Doc. There’ll never be another like you.

![]()

Bill Berg’s 1952 Les Paul GoldTop

Getting old has its drawbacks… but there are ALSO some lovely benefits to having friends you’ve known for 50 years.

Bill Berg and I have known each other from our Chicago South Side days, in the late ’60’s. I was working small clubs on the South and West Side, getting a minor reputation as the new white boy on the scene who could actually play the stuff right. Meanwhile, Bill, a few years older than me, had already befriended many of my employers, and his med-school training enabled him to provide medical care and advice to some of these guys, who often had scant options in that regard. Over the years, we kept in touch, through our moves to the east coast, and through our various marital and professional changes. Much in our lives had changed- but at some point in our evenings together, the conversation would inevitably turn to the old days. At that point, the various tall tales of shootouts in clubs, harrowing experiences on the road, and unsubstantiated rumors concerning mutual musician acquaintances would get ceremoniously rolled out. Our wives Melinda and Celia would roll their eyes, and as our scuttlebutting grew more vivid, they would decamp to another corner of the room… presumably, to engage in conversations more becoming of intelligent human beings.

Fast forward to a few months back, when Bill told me of his desire to bequeath to me his old guitar, from the South Side days. Not just ANY guitar, but his old ’52 Les Paul Goldtop.

Now, guitar geeks will instantly recognize that a ’52 Les Paul Goldtop is close to the top of the pantheon of iconic, collectable guitar models. Pristine, unmodified and well-cared-for examples are lusted after due to their rarity, and have become extremely valuable in the last few decades. (These days, ownership of valuable guitars has become the exclusive province of hedge fund managers, dentists, and aging rock stars… not musicians who made them iconic through actually playing them. But that’s another story, for another time.)

However, BILL’S ’52 Les Paul Goldtop was hardly pristine, unmodified, or well-cared-for. In the parlance of collectors, Bill’s guitar had been woefully “boogered”. Much of the boogery had taken place before Bill ever owned it. But the fact is that over the years, many of us- myself definitely included- have committed what in retrospect seem like venal sins to our now-collectable guitars. During the late ’60’s, instruments were considered simply tools to make the meager living their music afforded their owners. The idea of being reluctant to diminish the value of what might once become a valuable collectable was the furthest thing from our minds. But that, too, is another story for another day.

Fast forward to today, when FedEx delivered the box containing Bill Berg’s old, hardly pristine, hugely modified, not especially well-cared-for ’52 Les Paul Goldtop. Now, sitting here, looking at it’s completely decalled, ’60’s-out case, I can’t help but reflect on all the painful, bizarre and occasionally beautiful aspects of this thing we call “the aging process”.

Inevitably, like guitars, our bodies and our friendships morph over time, acquiring odd scars, modifications, and patinas from use. But there are still songs left to sing, new arrangements to work out, and fresh solos to play. Rock on Bill… and thanks for thinking of your old South Side buddy. I’ll always treasure your guitar!

![]()

Black Culture, and a Musician’s Responsibility

Today, a little over a week into “Black History Month”, I’d like to speak directly to my fellow musicians and friends here on FB.

The neighborhood I grew up in, the values of my parents, the sounds in the air I instinctively gravitated towards… all these influences left a profound stamp on who I am. In my late teens, I made the “decision” to forge a career in music… but it would be just as accurate to say the decision made me. 50 years later, I can reflect on how much I’m indebted to those music influences- for the opportunity I’ve had to occasionally stand on the shoulders of giants, and to learn the skills necessary to play my own music in their footsteps.

The music I chose (or, perhaps, the music that chose ME) is Black American Music. Blues, Jazz, R&B, soul music… many flavors, but they’re all rooted in the black experience, and were a folk music for black people, well before white people like myself found their way into the mix. As I see it, being allowed into that mix is an honor and an implied debt which I’ll be paying for the rest of my life.

I have many, many friends who have felt the same tug of gravity, and have forged careers around playing this music. All of us who have done so also know our society’s shameful social and economic exploitation of the architects and icons of it. With that in mind, I’d like to make a personal exhortation to all of you.

In recent months, 26% of our nation’s citizens voted to usher in a political climate of rejection of the interests of black people and black culture, unlike any time since the ‘50’s. I feel strongly that those of us whose lives have been enriched by black culture have a moral obligation to forcefully and consistently speak and act as counterweights to this exploitation. To do anything less than that is to implicitly reap the benefits of all the exploitation that has gone on before. Each of us can find our way to do this, and we certainly won’t speak with one ideological voice, when we do. But to remain silent, in order to avoid alienating potential fans, venues, or employment institutions is NOT an option, in my opinion.

As the great Frederick Douglass wrote recently on FB, “You either have to be part of the solution, or you’re going to be part of the problem.” Thanks for listening, friends!

![]()

Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, and a Nobel Prize

I was still 13 years old, in 1963, when my dad asked if I wanted to go with him to a concert of an old music buddy of his, Pete Seeger, at Carnegie Hall. Sure, why not?

I knew Pete as a family friend- a guy who used to stay at our house when he was in town, like many other of my parents’ friends. My parents had been “fellow travelers” with Pete, from labor union concerts of the mid-40’s, thru the Wallace campaign and Peoples’ Songs days of the late ‘40’s, thru the blacklist days of the early-mid ‘50’s. But, truth be told, by 13, my musical passions had already turned to the music of blues and old-time music pickers like Mississippi John Hurt, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Doc Watson. So, I wasn’t completely thrilled by the prospect of seeing Pete, with his serviceable banjo strumming, and sing-along performing style. But, this was a big concert, in Carnegie Hall… so sure. Why not?

At the end of Pete’s first set, he announced that he wanted to introduce the songs of a young songwriter, who was in the house that evening, and whose album had just been released. He proceeded to launch into a song entitled “Who Killed Davey Moore”, concerning the death of a boxer who I had never heard of. Coming after Pete’s comfortingly familiar favorites, however, this song brought me to full attention, and aroused the pure, passionate outrage that only a 13 year old can harbor. Pete now had me, as he announced another of this songwriter’s songs, entitled “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall”.

By now, the hair was standing on the back of my neck- a trick that only Blind Willie Johnson’s guitar playing had managed to accomplish until then. But- where the previous song about the boxer gave voice to all my righteous adolescent outrage- THIS song managed to distill every pure expression of what was evil in the world, as well as what was right, and beautiful, into a song that felt as old as the hills, or the heavens. Every image of dystopian ugliness, as well as every expression of noble sentiment and heroic impulse, seemed to be in there, to this thunderstruck 13 year old.

And then, the set was over.

My dad looked at me as the house lights went up, and could tell I was moved. He said “what did you think?” I must somehow have managed to express my awe, because he said “Well… should we go backstage and meet the guy who wrote those songs?” I was amazed that he thought we could do that… but of course, Pete was a family friend, my dad was an extroverted kinda guy, and it was actually quite easy.

Minutes later, I was shyly shaking the hand of the guy who wrote the tunes, Bob Dylan, who appeared as uncomfortable with the moment as I was. My dad noticed that there were a few printed copies of the lyrics to the Davey Moore song, and my dad wondered if Bob (we were on a first name basis by now) would sign a copy for me, as a souvenir. (Hopefully, I still have that copy somewhere.)

Anyway… all this youthful emotion and memory hit me like a ton of bricks, as i watched Patty Smith fight back tears and nerves, in order to deliver this amazing rendition of the song I first heard 53 years ago. I don’t know if it’s truly Dylan’s finest moment, as a songwriter… but it sure felt that way, as I listened to this…

![]()

George Martin, and Some Reflections on the Art of Production

2 years ago today, George Martin, the Beatles’ producer and arguably the most famous record producer who ever lived, passed away at the age of 90.

But, before telling you about George, allow me to digress for a moment…

——————————————————–

At age 7, my parents noticed that I was acquiring a lot of bruises, that never seemed to heal properly. True, kids do a lot of things that cause bruises. But this was different… a fact that was eventually borne out by medical tests. And, so began a long six months of painful procedures, extended hospital stays, and ultimately, an operation to remove my spleen.

One day, while recuperating in the hospital, my dad came to visit, and took me to a puppet show that was taking place several floors below. I sat in the front row with the other kids, with my dad sitting awkwardly next to me, obviously restless at having to sit patiently through the show. A few minutes into the show, my dad got up, and walked over to the side of the room. A minute later, he returned to his seat, and whispered in my ear, “Paul… do you want to go over to the side of the stage, and see how the puppets work?” I must have looked at him quizzically, because he began to explain that there were people behind the tiny stage, making the puppets work with their hands, and that you could actually SEE them from the corner of the room that he had just come from.

I remember being torn, because I really wanted to be sitting there with my dad– who never visited the hospital as much as I wished he did. So I certainly didn’t want to discourage him from visiting again, by appearing ungrateful for the time he spent with me. But I also really didn’t want to go to the side of the room with him, and watch how the guys were operating the puppets. I mean… how could you enjoy watching the puppet show, after you saw the artifice of how the show actually worked?

So, I stayed in my seat and watched the puppets, transported by the magic of the story.

——————————————————–

At age 18, I started playing in clubs in my South Side Chicago neighborhood, alongside older men who had previously been childhood heroes. There were many exhilarating moments on stage with these iconic figures, who I once only knew from the covers of record albums. However, along with the exhilaration came uncomfortable realizations. Men who had recorded some of the most powerful, riveting music I had ever heard were now here, next to me, sandwiching vapid jukebox hits between their powerful blues numbers. I couldn’t understand why they felt the need to “play to the people”; and after my naive, adolescent eyes were opened to the simple fact that these men were just trying to make a living, I struggled with how to view my former heroes in the same idealized light that I had, 2 years earlier.

The answer I gradually came to is… I couldn’t. The music I so dearly loved seemed to take on new and different meanings, now that I was seeing it from the vantage point of the guy on stage. I felt that very soon, I would have to make a decision. I could hold onto my fantasy of what I imagined the blues to be– which meant I’d have to stop playing with all my heroes– or I could choose to look at the music world I was gradually moving into with eyes wide-open.

Which one’s it gonna be, Paul…. the fantasy, or the reality? You can’t have both. But this time around, I chose differently than I did when I was 7.

For better or worse, I chose the reality of being a professional musician. And gradually, I began to realize that the magic in the music didn’t disappear– even when viewed from behind the scenes, where one sees all the angles of how the show actually works.

——————————————————–

Around this time, I began getting calls to play studio sessions. Many of them were at the iconic Chess Studios, the hallowed ground where Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, and Buddy Guy recorded. By then, I was fairly aware of the fact that the music world, as viewed from backstage, was not quite as glamorous as the view from the front row seats; so I was not especially surprised that the studios’ appearance was quite mundane.

What DID surprise me, however, was how the sessions were conducted in these mundane rooms. I imagined magic moments of lightning, captured in a bottle. But instead, the process seemed more like making a movie– short bursts of actual band music-making, interspersed with longer periods of technical adjustments, and arguments over arrangements… all accompanied by disheartening displays of every frailty and failing the human ego is capable of. Was this how my favorite Chess blues recordings were made? It certainly wasn’t what I had imagined, listening to them as a young teen, 5 years earlier. But the more I watched and participated in these sessions during the late ‘60’s, the more I began to suspect the answer was “yes”.

Clearly, some sort of magic must be taking place on a regular basis, in order to bring forth from these haphazard recording sessions an exciting, tight-sounding, cohesive record. And by having the opportunity to watch men like Willie Dixon, Gene Barge, and Charles Stepney at work, I began to realize what that “magic” was. It was called “production”.

——————————————————–

Which brings the story back around to record producer George Martin.

As he was for practically every recording artist in the world, George was a hero to me and my bandmates in the Unknown Blues Band. The string arrangements, the classical music flourishes, the remarkable juxtapositions of those sophisticated elements with the edgy rock and avant-garde sensibilities of the tracks they embellished… these details were all immediately apparent to me and my musician friends, made all the more impressive by the fact that they were so unremarked on by the general public.

Upon hearing of his death, I immediately thought of the time in the mid-80’s when we were asked to play at the wedding of George’s son Greg. The opportunity to meet the man who had taken the Beatles’ lightning in a bottle– and alchemically combined them with his own very different skills, to craft all those iconic recordings– was exhilarating. But… what was he actually like? Would the man who produced the Beatles, Elton John, Pete Townsend and Dire Straits want to take time from his own son’s wedding to hang out with a bunch of less-than-household-name musicians? And what if he turned out to be a self-absorbed jerk?

Well… he wasn’t. In fact, he was a wonderful cat, who clearly enjoyed talking endless peer-to-peer shop with musicians who he obviously had never heard of. Yes, of course, there were a few Beatles stories that cropped up in the conversation. Being someone like George Martin means you can never not be “that guy”.

But what I most remember is his delight in talking about his work with “The Goon Show”, a BBC comedy show that featured Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore, and was considered to be the forerunner to Monty Python. To hear his delight in telling those Goon Show stories, you’d think that was the highlight of his entire career. Who knows… maybe it was?

A truly lovely man. Rave on, George Martin, wherever you are.

![]()

Shirley Caesar, my Mom, and a Bad Memory

The date April 28 will always serve as a reminder for me of my most mortifying memory lapse.

On that day, in the year 2000, I was at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. That year marked my 15th pilgrimage to the Fest, and with each year, my sadness at the devolution of the festival became harder to ignore. I had been catching my usual favorites at various stages around the Fairgrounds that Friday, biding my time until Shirley Caesar was due to perform in the Gospel Tent. For me, seeing Shirley Caesar perform in the tent was an absolute must-see, and held the promise of rekindling the unique community spirit that I experienced when I first started attending the Fest in the mid-’80’s, but felt increasingly missing as the rest of the world started discovering it.

I made sure to get to the Gospel Tent early enough to get a good seat. When Shirley hit the stage, the crowd’s roar of delight and adulation confirmed that I was in the right place, for my “rekindling” experience. Shirley’s appeal to her churchgoing fans and followers was deep and powerful, and the theatrical tricks of the trade– which every experienced gospel performer has in their toolkit– were so interleaved with moments of genuine inspiration, that one would be hard-pressed to tell where the tricks left off, and heartfelt spirit connection began. That is to say, she perfectly performed the ritual which her audience was there to be part of… and which I was there to be part of, as well.

Around 20 minutes into her performance, at the end of a knockout gospel number featuring an extended praise vamp, Shirley said to her audience “I want to ask each and every one of you in the audience a question.” As the last few “Hallelujahs”, “Praise God’s” and smatterings of applause faded to a hushed silence, she said “I want to ask you a question. How OLD is your mother today?” I knew that this tug at the heartstrings was also a segue into one of Shirley’s many “Mother” songs, such as “No Charge”, or “Don’t Drive Your Momma Away”… and, of course, so did her fans. Nevertheless, I was happy to roll with the obvious emotional manipulation, and reflected on my own answer.

As I did so, I felt a cold shiver. Apr 28! My god… my mother’s BIRTHDAY is Apr 28! Let’s see… she was born in 1920, so that would make her… Oh LORD… that would make her exactly EIGHTY YEARS OLD… TODAY!!! How could I have overlooked that??? And why hadn’t this come up as a discussion topic in the last 6 months, with my siblings?

And then, I remembered. After we sibs had all engineered a huge surprise party for her 70th birthday, Mom had made us promise that we wouldn’t do another extravaganza like that, so she could always remember that special 70th.

Yeah, but STILL!! How could you forget her 80th, Paul?

Well, I eventually calmed down, and after Shirley’s performance was over, I walked out into the sunlight, humbled by the frailties of the human brain, and by the the power of the human spirit… with, maybe, a bit more appreciation for parapsychology thrown in, for good measure.

Mom left us on April 28, 2015, on her 95th birthday. I doubt I’ll ever forget her birthday again. Love you, Mom!

![]()

Memorial Day, and a German Car

This morning, my usual exercise ritual was accompanied by TV coverage of the Memorial Day events at Arlington Cemetery. Watching them, my mind wandered.

I thought of my dad, who served in WW2, and of the countless letters to his fiancé, my mom, which my sister Jodi laboriously compiled and transcribed, and which I’ve recently been reading. I thought of the powerful forces in Europe which he and his fellow soldiers– most still in their teens– were so steadfastly committed to vanquishing.

My mind then wandered to my own late teens, when I decided to buy a used VW Beetle. Mentioning the purchase to my dad, I got a bit more pushback than I anticipated. Not because of the money, or the quality of the actual car… but because it was German-made.

My family is Jewish, and so I was quite aware of our connection to those who were lost in the Holocaust. But I had always known my dad to be a very cerebral person, and was therefore surprised to hear his uncharacteristically emotional response- 23 years after the war ended- to his son purchasing a car built by the country he had fought against. My dad’s response stuck in my mind, and continued to live on in my mind, long after the car was sold for junk.

Thinking of that Beetle led to a recollection of 15 years ago, when I purchased my then-12-year-old Audi. That purchase also got some pushback– in the form of teasing from friends, who associated the name “Audi” with wealthy yuppies, rather than blues musicians. Furthermore, I found out, shortly after purchasing it, that the maker WASN’T Scandinavian, as I had assumed… but, rather was German. Once again, I experienced that ambivalent twinge, for purchasing a German product. However, the car was built like a tank, served me well for over 10 years, and subsequently spoiled me for driving any other brand.

The war that my dad and so many others fought over 70 years ago solidified the reputation of the US as “the leader of the free world”. Germany, Italy, and a number of other European countries were left with a shameful legacy– not just of defeat, but of having inflicted unspeakable horrors on the world, and to tens of millions of its former inhabitants. How could a country like Germany ever recover from that history?

Somehow, it has. And then some. To the point where thoughtful observers of the world order are now speculating aloud that Germany’s Prime Minister Angela Merkel may well be the leader of the free world we are now shape-shifting into. They point to the country’s responsible approach to climate change, nuclear power concerns, aggressive commitments to the institutions of democracy and a stable world order, and many other metrics.

The humility and painful self-reflection forced upon the German people and their government, following the catastrophic overreach of the Third Reich, seems to have created an admirable society. Meanwhile, our own society, crippled by hubris and an almost total lack of self-reflection on our own history, slips into sad and shameful abrogation of the democratic values we fought 2 world wars for, and claim to cherish. The highly publicized discordance at the recent NATO summit might well be seen as a tipping point– where our nation petulantly disavows its former mantle of moral exemplar, while another nation reluctantly picks up the hot potato so casually discarded by ours.

70 years has brought about quite a change. Certainly, there’s cause for optimism in Germany’s remarkable turnabout on the world stage– and, and, perhaps, by extension, for our own society as well. Hopefully, though, we won’t have to sink to the same dark, demonic depths that Germany’s society did, in order to make our own turnabout.

At any rate, these mental meanderings make me feel a bit better about driving a German car. Sorry, dad.

![]()

Steely Dan, and an Impulse Decision

In 1971, after a brief lifetime of playing in blues and R&B bands on the south side of Chicago, my then-girlfriend and I were ready for a change. Rational thought dictated a move to a major urban area music scene for me, or a grad school for her. For some reason, we chose instead to pack our worldly possessions into a VW bug and move to a spot 8 miles up the side of a mountain, in rural northern VT, where we built a geodesic dome.

For a couple of years, we lived “off the grid”… at first, quite literally, with no electric power. But, even after we eventually hooked up the juice, we remained quite disconnected from popular culture of any sort for several years. (To this day, when a pop song or movie reference is unfamiliar to me, I ask “was that between 1971 and ’73?”)

Around 1974, shortly after plugging back in, my girlfriend developed a strong infatuation with a record called “Pretzel Logic”, by a group calling themselves Steely Dan. I recognized instantly the William Burroughs-inspired band name, and was further intrigued by the obvious Dylan reference in the album she acquired shortly afterwards, “Can’t Buy A Thrill”. These were smart guys, and I grudgingly admitted that the music was indeed awfully clever. But I was quite a creature of musical habit in those days (and still am, I suppose) and the music clearly struck me as “white rock”… seemingly not beholden to the instrumental textures or vocal conventions of black R&B in any way. As a result, I just couldn’t dig it. (Elaine, you certainly were ahead of me on that score.)

Things started to change a bit with “Katy Lied” and “The Royal Scam”, but it wasn’t until “Aja” in 1977 that I was completely, head-over-heels on board. Had the rhythm section playing– clearly closer now to R&B than to rock– actually become more slinky, funky and sensuous? Or was it that I just never noticed how good it was before? Were the harmonic underpinnings– obviously inspired by Ellington and Wayne Shorter, and other of my jazz heroes– much more ambitiously and fully realized now? Or was it that I just missed it in the earlier tunes, because the timbres were closer to rock than jazz?

Hard to say. All I know is that by then, I too was writing music underpinned by funk and R&B rhythms– but with harmonic and melodic ideas more beholden to jazz than pop music– and Steely Dan had clearly staked out similar turf, with artistic and commercial success beyond what anyone could have predicted. Their success was an exhilarating, encouraging sign for groups like the one I formed in 1977 (soon to be renamed Kilimanjaro). But at the same time, the visionary arrangements, instrumental and vocal track production values, and unprecedented sonic excellence set a terrifyingly high benchmark for anyone bold enough to compete on similar turf. This I could dig… and did.

Among my music friends, the widely divergent opinions of SD’s music seem to fall into several distinct categories. There are the music nerds, who appreciate the ambition, complexity, and innovation of the music… lyrically, instrumentally, and compositionally. There are the hit radio fans, who were initially sucked in by the incredibly well-crafted rhythm tracks, and eventually grew to love them as pop anthems. On the other hand, there are those who hate the music, seeing them as formulaic pop pablum. (I find myself wondering what “formula” they’re thinking of… but that’s another tangent, for another time).

But whatever one thinks of the work, these 2 guys have raised the bar of sheer ambition in pop music to a dizzyingly high level, putting them in the category of the Beatles, and precious few others. And, like the Beatles, Becker and Fagen decided that their studio creations could not be successfully rendered live, and stopped performing as a band in ‘74. They did very little touring for 30 years afterwards, and even after that, little in the US.

Almost exactly 3 years ago, I noticed that the group was playing dates in the Northeast, with my Chicago buddy Bobby Broom opening the show. At 4:20PM, as my wife Celia and I were discussing what we should do for dinner, I jokingly pointed out that Bobby and the Dan were both performing at 7:30PM that evening in Gilford, NH. Gilford is 2 3/4 hours away… so if we left right that minute, we could just make it in time to catch the show.

By 4:40, we had bought tix and a parking pass, printed them out, jumped in the car, and drove like a banshee to Gilford. We got there just as Bobby was starting his set… which was an excellent one. Steely Dan, of course, sounded fantastic. Their deeply ambitious music was made all the more so by re-arrangements that featured each band member, much as Ellington’s did. The arrangements didn’t always feel congruent with the iconic arrangements we’ve heard for decades… but huge props to Fagen and Becker for going for it– in true, re-inventive jazz tradition.

Now that we’ve lost Walker Becker, I’m so glad we made that unplanned trip.

Thinking back, I’m reminded of a similarly spontaneous trip to catch a Prince show, not long before he passed. Our iconic musicians are not going to be around forever. Let’s not pass up opportunities to catch them while they’re still with us.

![]()

Love Letters, Wow, Flutter, and Analog Tape

Ever run across a letter you wrote to a childhood sweetheart, 50 years ago? Or find some old photos of a house you lived in as a kid, and marvel at rekindled memories of once-familiar rooms? I just had a similar experience, thanks to long-time Chicago buddy Bill Berg.

Apparently, Bill just found an old reel-to-reel tape of my first vaguely serious band, called Mahogany Hall, fronted by my now-departed music mate, Jeff Carp. On the tape are 3 tunes, recorded at the Chess Records studio (probably in ‘67-‘68) as a demo for a possible recording contract (remember those?). Bill had the disintegrating tape treated by a restoration pro, and then made dubs of the tunes, which he sent to me in MP3 format.

Listening to these, I am reminded that this was the era of Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago… horn bands that were creating pop music outside of the R&B/blues mold that our band generally played. Thus, a couple of odd-sounding tunes got developed, in hopes of interesting A&R execs at what were once called “the major labels”. I had completely forgotten about these tunes, until now. Remembering them is like suddenly remembering a dream you had last night… except last night was actually 50 years ago!

The recordings were done sometime in ‘67 or ‘68, and due to degeneration of the tape, there’s quite a bit of what was once called “wow and flutter” (remember THAT term?) back when analog mediums like tape and vinyl were the norm. In layman terms, that means there’s quite a bit of warbly “out-of-tune-ness”, as well loss of fidelity and frequency response. And, speaking of wow– there’s some distinctly “non-wow” moments in the playing of the teenagers who comprised this band… myself definitely included!

Still, though the old photo is tattered in places, there’s enough there to evoke a lot of memories. Isn’t that would you’d expect, upon discovering an old love-letter?

![]()

Shashlik, and the Hippocratic Oath

In 1991, my band Kilimanjaro, along with tenor sax player/vocalist Big Joe Burrell, toured Russia for several weeks. To say it was an eye-opener would be a massive understatement. (Perhaps, if I can find some time, I’ll write a piece about that fascinating trip).

However, right now, I want to write briefly about a specific incident on our trip: how that incident caused me to reflect on my own cultural assumptions as an American, and how those cultural assumptions seem to have changed over the last 26 years.

Our band was returning to our hotel from a gig we had just played in Moscow. It was late, and the long day of travel, load-in, setup, playing, tear-down and pack-up had left us all quite hungry. To say that food options were slim would be yet another understatement… and at that time of night, appeared nonexistent. Any and all entreaties to our translator/guide Tanya as to food options were met with stern disapproval… as if the mere desire to eat something at that time of night was a sign of moral turpitude.

While rounding a corner in our van, in a dark wooded area close to our hotel, we spied the flickering light of an open fire coming from what looked like a sawed-off barrel. A few people were huddled around the flames, poking at something. We asked Tanya what it was we were seeing, and she responded with disgust, “Oh, those Georgians… probably selling shashlik”. Hungry musicians that we were, when sensing the possibility of a flame-broiled late-night bite, we all shouted “Yes! Let’s turn around and go back there!”

But Tanya would have none of it… explaining in a condescending tone that “those people” should be ashamed of themselves, for exploiting peoples’ hunger for profit. It was one of many glimpses our trip offered into the cultural assumptions of our Russian hosts, and by extension, the cultural assumptions of we Americans.

In relating this story to friends upon our return to the US, I realized that Tanya’s response to the shashlik peddlers bewildered them, as well. “Why was she so unwilling to stop? Was it because she disliked Georgians?” Well, in part, yes… but probably no more than other cultures’ sentiments towards swarthier, earthier immigrant populations from southern regions. “But why was she so disapproving of the idea of selling food, late at night?” That one was a bit more difficult to explain, and my attempt at explanation was at best a speculation into the difference between the Russian and American psyche.

Tanya, it seemed, viewed hunger as inevitable– a regrettable but inherent part of the human condition. When viewed through that lens, anyone who was ethically challenged enough to “pander” to a musician’s hunger at this ungodly hour of night must surely be a horrible person. Sure, people get hungry, so the thinking presumably went… but it’s immoral to EXPLOIT that hunger for personal gain. With our stomachs grumbling loudly, this slant on the ethics of selling BBQ meat at night was obtuse to us, and appeared equally foreign to the friends who I related the story to afterwards.

In attempting to make the Russian cultural assumption a bit more clear to my friends, I said “Look. In our culture, we have doctors, who take a Hippocratic Oath to care for the sick. We accept that they also need to make money from their work. However… what would we think if a doctor saw a man lying on the pavement, in distress, and tried to dicker with the man about his ability to pay, before supplying care? Granted, doctors are entitled to make a living… but wouldn’t that be an unthinkably horrible example of exploiting the man’s distress, in order to line his pockets?”

In 1991, that medical analogy struck me as a valid way to couch the ethical quandary of making money off another’s need… using an example that our society presumably found unthinkably horrible, when taken to its logical extreme. 26 years later, it’s remarkable to me how our society seems to have grown accustomed to that logical extreme as an acceptable point of view– and NOT particularly horrible or unthinkable– when considering the role of our “health-care system”.

Our society has found endless ways to supply flame-broiled meats to hungry musicians, late at night, at remarkably affordable prices. Hopefully, we can find a way to supply life-preserving medical care to our citizens, at times of need, without bankrupting our people, our government, or our collective moral compass.

![]()

Muhal Richard Abrams

In the mid-late ‘60’s, I lived in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago. Although ostensibly going to college, my musical pursuits soon overshadowed my academics, and I eventually found myself playing in blues clubs more than attending classes.

My single-minded focus also applied to the music I listened to, as well. Chicago-style blues, as played all over the South Side by men such as Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Earl Hooker, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, was my abiding obsession for several years.

During that time, I had several musician friends and bandmates who shared my love of blues, but also had their ears open to the jazz sounds which surrounded us. One of these bandmates shared an apartment with saxophonist Joseph Jarman. Joseph performed with a collective of musicians which included Lester Bowie, Fred Anderson, Roscoe Mitchell, Malachi Favors, and a pianist named Muhal Richard Abrams. These musicians began to refer to their collective as the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians… AACM, for short. The performing unit called themselves the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and adopted as their mission statement “Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future.”

Art Ensemble of Chicago performances were often multi-media spectacles, mixing African dance and recorded environmental sounds with highly atmospheric jazz playing, in a style very influenced by John Coltrane’s groundbreaking innovations.

I didn’t always understand, or even like, everything I heard and experienced at these shows… but they definitely opened up the ears of an impressionable young blues guitarist.

Over time, many of those musicians became nationally known and revered, and the Art Ensemble and AACM continue to exert a profound influence on how jazz is played in the 21st century.

RIP, AACM president and National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Fellow Muhal Richard Abrams.

![]()

Maple Syrup, and a Life’s Work

In 1971, I was immersed in a professional music career in Chicago, but was casting about for a change…. presumably, another busy music scene to wade into. My then-girlfriend had just finished college, and also felt ready to make a fresh start somewhere else… presumably, a university with a strong graduate program. However, the “back to the land” movement was in full swing, and had swept up many of our friends in its powerful, heady wake. Ignoring the logic of career arcs and academic pursuance, we opted for a dramatic lifestyle change, without any clear view of what lay ahead. We bought land halfway up a steep mountain road in northern Vermont– and there, with a small amount of savings from my 6 night/week gig, armed with the Whole Earth Catalog and some borrowed tools, we built a geodesic dome in which to start our new life.

The next spring, we decided to try our hand at tapping trees, to make maple syrup. I had been told it was hard work– tapping the trees, setting out the buckets, collecting and lugging all the sap, chopping and splitting all the firewood, constantly monitoring the pan to make sure the syrup didn’t go a bit “too far” and be ruined– but I didn’t really realize how MUCH work it was until we actually DID it. It was rather sobering to see how few pints we wound up making after all the effort we had put in… but it certainly made us appreciate the delicious reward all the more.

That summer, some visitors from the city came to visit. The next morning, as the plate of pancakes was laid out on the table, we ceremoniously brought out a pint Ball jar, containing the precious elixir we had made that spring. We explained the process, and the time it took to make the syrup… but were a bit underwhelmed by our guests’ response. One of my friends asked– while he poured a generous helping of syrup on his stack– “why is the stuff so expensive when you buy it in the store”?

Brushing aside the annoyance at our city slicker friends’ question, we began to describe the whole process, up to the point where the sap actually gets reduced, by boiling, into syrup. Our friends– who hadn’t seem particularly impressed by any of it until then– asked “How many gallons of sap do you need to boil down, in order to make a gallon of syrup?” I replied “40 gallons”. One friend looked at me incredulously, as I explained that the ratio of sap to syrup was 40-to-1… so, yes… 40 gallons of sap needed to be boiled down, in order to make a gallon of syrup.

Clearly astonished, the friend slapped his forehead and said “Jeez… then why do they bother to do it at all!”

I think of that morning often, as I teach jazz guitar to my students. Often, it begins with an innocent-sounding question, like “what scale is that that John Scofield is using to solo over his tunes?” Or, “How many chords do you need to know, before you can play all these jazz standards?” Sometimes, my friend’s astonishment comes to mind when a well-meaning acquaintance expresses surprise that “I still feel the need to practice”. At those times, the thought occurs to me that if I was to describe the whole process, and elaborate on the many “40-to-1” issues a jazz guitarist has to deal with to play the music, the response would once again be “Jeez… then why do they bother to do it at all!”

Perhaps it’s just as well that most aspiring guitarists have no idea what’s involved when they first set out to make complex music, such as jazz, on the guitar. If they actually had a clear-eyed view of the work required, many people would opt to turn around, before the road up the mountain got too steep.

For those that persevere on the journey, however, there are sweet moments of reward that make all the work worthwhile. And for a teacher of this music, it can be a deep well of satisfaction to watch a student turn onto the road that leads up the mountain, eyes wide open to the challenges, armed with a Real Book and some Wes recordings, starting a life’s work.

![]()

Clouds of Hashish Smoke… From Both Sides Now

The first few months of 1968 found me living in a dingy apartment on my hometown of Chicago’s south side, along with 2 guys I had befriended during our freshman year at University of Chicago. While Peter and David were in their second year at UC, I had dropped out after a revelatory trip to Mexico over Christmas break, and had just taken a day gig as a messenger boy for Arthur Anderson, working out of their skyscraper-size office building downtown. At night, I was playing blues clubs on the south and west side, making $22 per gig, working alongside men two and three times my age, learning musical and personal skills which I still use to this day.

One morning around 5:30AM, my girlfriend and I were awoken from a sound sleep by a loud, insistent knock on the apartment’s front door, followed by a voice bellowing “Open up!”

Living where we lived, one always felt a certain level of anxiety about what dangers might await in the streets outside our door. Petty burglars, late-night drunks, enraged street people, traumatized Vietnam vets… all these variants and more would present themselves in the neighborhood, at any and all hours. At this unthinkably early hour, on this frigid morning in the middle of a bitter Chicago winter, our front door seemed to offer flimsy protection against whatever threat was on the other side.

Alarmed, I leapt out of bed, threw on some jeans, and yelled “Who is it?” The voice came back “CHICAGO POLICE! OPEN UP, OR I’M KICKING THE DOOR IN!”

The next few minutes or so are still a blur to me…. but I am able to reconstruct most of the basic details.

Undercover Chicago Police Department officer John Zandy and his backup partner quickly stepped inside the opened door, announced that my roommate David and I were being arrested on the charge of “Sale of a Narcotic Substance”, and ordered us both to present our hands forward to be handcuffed. 30 minutes later, we were being processed at the jail at 26th and California, and put into separate cells.

While in the back of the patrol car, I started piecing together how I had gotten into this mess.

======================================================================

My first year of UC was something of a disappointment for me… and, I imagine, for my teachers. I had done very well on my entrance exams, and as a result, was placed into more advanced levels of the courses I most valued– namely, math and chemistry. After all, these were the courses that I had pictured as holding the key to my future. (Funny, right?) The main reason I was so pleased with my performance on the tests was that I would now be able to swim with the big fish, instead of meandering about in the slower backwaters with the “deadwood”. Yeah… deadwood. You know– those poor souls who had to continually put their noses to the proverbial grindstone to get good grades. Unlike me, who had managed to sail through my high school courses without breaking a sweat.

However, I hadn’t yet apprehended what would later seem so obvious– namely, that now that I was swimming with the big fish, I would be expected to paddle hard to keep my head above water. To my great disappointment, the ability to even so much as break into a doggie paddle eluded me, for my entire first year of school.

Of course, it wasn’t like I was doing NOTHING that first year. I actually was quite busy with stuff that many college freshman presumably do– things like making friends, reading a bunch of things that were not related to my actual courses, and “finding myself”. The first pursuit mostly involved finding other musicians at school who were interested in the music I was interested in– that is, Chicago blues, as played in bars and clubs all over the south side. By the 2nd half of the year, I had acquired a fake ID through an older musician who had befriended me, which allowed me to get into the 43rd St blues clubs, such as Peppers’ and Theresa’s, as well as places like the 1815 Club and Sylvio’s on the West Side. At that point, my search for musicians was no longer limited to school associations. Once that ID was in my wallet, these clubs were where I started spending as much time as I could.

Getting that fake ID was certainly my gateway to getting into– and soon afterwards, gigging in– Chicago’s blues clubs. But the ease with which I was able to obtain the ID also exposed to me how things worked all over my hometown; whether on the street, in the courtrooms, or in the backrooms of power, everything could be had at a price, if you knew where to go, and who to ask.

This generally cynical view of “the way things worked” was especially common in the black community which I was increasingly immersed in, once I lived off-campus. One night, at a party during my 2nd year at school, a hip-looking dude who I recognized from the music scene came up to me and said “hey, my man… I like the way you carry yourself.” Once he had my attention, he said “Lookie here. Do you know anyone who can hook me up?” And, as a matter of fact, I did. My roommate David, an extremely bright and precocious fellow who had lived a somewhat sheltered life with his family in a wealthy Chicago suburb, had recently started dealing ginger-snap-sized rounds of hashish, which he was getting direct from someone in Morocco. I gave the guy, who identified himself as Omar, our apartment’s phone number, and felt a glow of pleasure for having enhanced David’s burgeoning customer base.

A few weeks later, the phone rang. An unfamiliar voice asked for David, and upon being informed that David wasn’t home, said “hey, man, this is John. I’m a friend of Omar’s, and he said David could hook us up for a party we’re having tonight.”. I told him that David would be home later, but I wasn’t sure when. John started to explain that the party just “wouldn’t be the same” unless David could hook him up, and pressed me for specifics of when he could swing by. My protestations of inability to provide a time were met with more pleadings of “come on, dude… can’t ya help a brother out?” Finally, John said “hey, man… you know where he keeps his stash, right? Why don’t you just hook us up yourself, from his stash, and we’ll give you a little extra taste, on top of what we normally pay your buddy”. Being fairly broke myself, and growing weary of resisting his pleas, I said “Sure, come on over”. A few minutes later, he did.

And that was the last I heard from or thought about John Zandy and his partner Omar until a few months later, when they knocked on our front door at 5:30AM on a frigid winter morning.

======================================================================

The word among Sam Adam’s colleagues was that he was one very odd duck– but an impressive lawyer.

The “odd duck” reputation stemmed from rumors that he lived in a predominantly black community on the south side (and reportedly refused to reveal the location to anyone outside his family) despite the fact that his income certainly enabled him to live in a “nicer” neighborhood. For someone like me, that choice didn’t appear “odd” at all. It was basically the same choice I myself had made– as had my parents during my childhood years.

The “impressive lawyer” part stemmed from his inclination to seek out cases pertaining to civil liberties and racial equity– often with the lofty intent of overturning oppressive laws and policies. Though it wasn’t immediately clear how my legal predicament fit any of those descriptions, my dad was somehow able to arrange a meeting with Sam, in order to to discuss the charges against me, the penalties I might be facing, and whether he would be willing to take my case.

In most states, people arrested for a first offense of selling drugs like pot were typically allowed to plead guilty to a reduced charge of possession, and given a light sentence… perhaps, even probation, without serving jail time. However, as Sam went on to explain, 2 factors made my own situation considerably more grave.

The first was the fact that under Illinois law, hashish– unlike pot– was considered to be a narcotic, and therefore was treated with the same legal severity as heroin, cocaine, and other “hard drugs”.

The second was the fact that the political and racial climate in Chicago leading up to the 1968 Democratic Convention had just propelled a “law and order” candidate named Edward Hanrahan into office as Cook County States Attorney. Hanrahan will be remembered by most people for his role in the criminally one-sided police gun battle which killed Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in 1969; but his immediate effect on me personally was his campaign promise to eliminate all plea bargaining for drug offenders. If Hanrahan was to follow through on this campaign pledge– and refuse to bargain sale cases down to a guilty plea of possession– then I would be unable to avoid facing the charge of “sale of a narcotic substance”. That charge carried a typical sentence of between 2 and 10 years in Cook County Jail, without possibility of parole.

But… but… I WASN’T a drug dealer! My roommate DAVID was the drug dealer! I was just… well… helping out. Does that actually make me as guilty as the ACTUAL dealer? Actually, as Sam explained… yes. It does.

But… but… I didn’t WANT to make the sale! John Zandy PERSUADED me to make the sale, that I didn’t really want to do! Isn’t that actually ENTRAPMENT? Actually, as Sam further explained… no. It isn’t.

The enormous consequences of my stupidity were hitting home very quickly, and very hard. As impressive a lawyer as Sam Adam may have been, his bedside manner was not exactly comforting, and his brusque (though well- reasoned) explanations of what I now was facing were simply too frightening to wrap my head around. Like everyone, I had heard and read about what happens to people in inner-city jails… and as a physically small 19-year old white kid, I was frozen with terror. I had just returned from a trip to Mexico, and I immediately began speculating on where I could spend the rest of my life outside the US as a fugitive.

Sam certainly wasn’t doing much to reassure my dad and me. But… were there really NO legal options? Wasn’t there ANY way of fighting this?

Actually, Sam said, he DID have an idea. It was something he’d been thinking about for many years, in fact. It was something that he felt could– and SHOULD– be pushed through the judicial system. Something that he would be willing to sign on to, without asking any fee. But it represented a tremendous risk… a risk that would unfortunately be borne solely by me.

“You see”, Sam began. “Illinois law presently allows a degree of latitude in sentencing, for someone who pleads guilty to the sale of a narcotic. Typically, 1 to 2 years in jail, with possibility of parole even earlier than full term. However, if one pleads INNOCENT to the charge of sale– but is found GUILTY at trial– the law stipulates a mandatory 10-year sentence, without possibility of parole.” Warming to his point, Sam further explained, “This wide discrepancy in sentencing effectively forces many people, much like yourself, to plead guilty, even if they felt they had a case to make.”

As Sam reached the crux of the argument that he had been turning over in his mind for several years, his voice rose in pitch and volume. “And FORCING a defendant to plead guilty, when they feel that they are INNOCENT”, Sam thundered, “is exactly what the Fifth Amendment is designed to PROTECT against! I would LOVE to take a case based on that proposition all the way to the US Supreme Court. And, hopefully, we would succeed in getting this sentencing structure– this TRAVESTY of justice- CHANGED.”

For a moment, I was swept away by his fervor– and by the thought that my dad and I could partner with Sam to heroically effect change within a manifestly unjust system. But… what if we lose? The look on Sam’s face, and the weary shrug of his shoulders, was confirmation that my question was a rhetorical one. Sam Adam, my dad, and I all knew the answer already.

======================================================================

The conventional wisdom for any criminal defense is to seek as many continuances as the court will allow… for a multitude of reasons.

For one, the more time that elapses after the date of commission of a crime, the more time a lawyer has to build a case that the client has taken steps to “turn their life around”. (Shortly after agreeing to accept me as a client, Sam made it very clear to me that I would absolutely need to return to school, sever ties with my dealer friend David, cut my hair, and move out of the apartment where the sales had occurred.)

But in my particular case, the seeking of multiple continuances had another strategic function. As time went by, the hard-nosed “no plea bargains” pledge that Hanrahan had rode into office on would likely weaken, and the DA’s office might become a bit more flexible. Since I had basically choked at the idea of being the sacrificial guinea pig in Sam’s grand scheme, an eventual plea bargain down to the charge of possession was really our best hope.

And sure enough, after several continuances were sought and granted, the possibility of a plea bargain with the DA’s office was floated.

By now, almost a year and a half had gone by. I was back in school, ties with David had been severed, hair had been cut, and I was now living in a new apartment, around the corner from my old one. Equally important, my case had gotten transferred to a Judge Kaufman… known to be a kindly man, and especially lenient to nice Jewish boys like myself. His lenience in my case took the form of allowing me to plead guilty to a charge of possession– still a felony by Illinois statute, but a damn sight better than what my prospects looked like 18 months earlier. My trial date was scheduled for the next month.

By the time of that final court date, Sam appeared fairly confident of what Judge Kaufman’s decision would be. The “lengthy passage of time” between the original offense and the final trial– and Sam’s apparently convincing argument for my “life turnaround”– were both mentioned in the judge’s remarks, before delivering his decision.

As my dad and I held our collective breath, the verdict was read… 3 years probation, and no hard time.

======================================================================

Truth be told, the imposition of 3 years of probation in the Cook County Correctional system was more than just a reprieve from the horrors of Cook County Jail. It actually proved to be a blessing in disguise, in its own right.

Over the years, I had employed various strategies for dodging the Vietnam War draft. The first was my 2S student deferment, which expired when I left school. Next was an attempt to reduce my weight to 113 and physically disqualify myself; and when that failed, I paid several visits to an anti-war shrink, resulting in a letter with a diagnosis of paranoid psychotic tendencies (which scared my dad, despite my warnings that the letter was merely a ruse). Eventually, it became clear that each strategy was only a temporary patch, and nothing more. My 3-year probation sentence, however, proved to be the final fix.

The Correctional system’s adamance in the face of pressure from the US Selective Service truly warmed the heart of this cowardly war objector. Their refusal to allow their charge to be removed from the probation program prevented me from being considered for military service until the draft was finally ended, two and a half years later.

Which just goes to prove the truth of that old adage from the ‘60’s– “every cloud of hashish smoke has a silver lining”.

![]()

Reminiscences of Matt “Guitar” Murphy

In the early months of 1970, after freelancing in south-side Chicago blues clubs for several years, my drummer friend Kennard Johnson gave me a tip on the down-low concerning a band he was playing with 6 nights a week, whose regular guitarist would soon be moving onto a national, hi-profile gig. The band was called “King Tut and the Carburetors”, and they played some blues, a lot of current R&B, and some jazz tunes as well, when called for. The pay was good, compared with what I had gotten used to, but the hours were 10PM-4AM, and 10PM-5AM on Saturday nights. Long, long hours. Was I interested?

Along with my bassist friend Clyde Stats, I drove out to the club, to check Kennard and the band out.

The band was just a trio, with Tut simultaneously playing complex bass lines like James Jamerson and singing like Stevie Wonder, and Kennard playing powerful drums. Without a keyboardist, the guitarist had a big job. His name was Matt “Guitar” Murphy, and listening to a couple of sets with the band was enough to let me know that if Matt were indeed to leave, I would have VERY big shoes to fill.

I knew Matt by reputation, because he had already had a long career playing with Memphis Slim, Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Parker, Ike Turner, Bobby Blue Bland, Muddy Waters, and many others, and his name was well-known to the small group of musicians who were passionate about blues lore in those days. However, here Matt was, in Carol’s Lounge, not only playing blues, but current pop material, jazz standards, an occasional country tune, and virtually everything else that the gig required over 5-6 hours of music per night. The fact that Matt handled it all with aplomb, facility and zest– evidencing no apparent preference for any one of the styles more than another– wound up making a huge impression on me… one that would last a lifetime.

Well, Matt wound up taking the gig a few weeks later, and left Chicago for good. Matt’s new gig was as a featured member of his long-time music partner James Cotton’s band, and lasted for many years, until he found newfound fame (and hopefully, a bit of fortune) from a featured role in “The Blues Brothers” movies, and subsequent touring.

Once Matt left, the gig was mine, and I stayed in it for a year or so, until I had saved enough money so that my girlfriend and I could make a long-dreamed-of move to rural VT, to begin a new life. But that’s a whole ‘nother story.

Matt’s incredibly long, illustrious career as sideman to virtually every artist in the blues world puts him in rarified company, for people like me. But equally admirable was Matt’s never-ending pride in his musicianship, his physical shape, and his relationships with his fellow man.

RIP, Matt “Guitar” Murphy.

![]()

Big Bill’s 1957 Benefit Concert

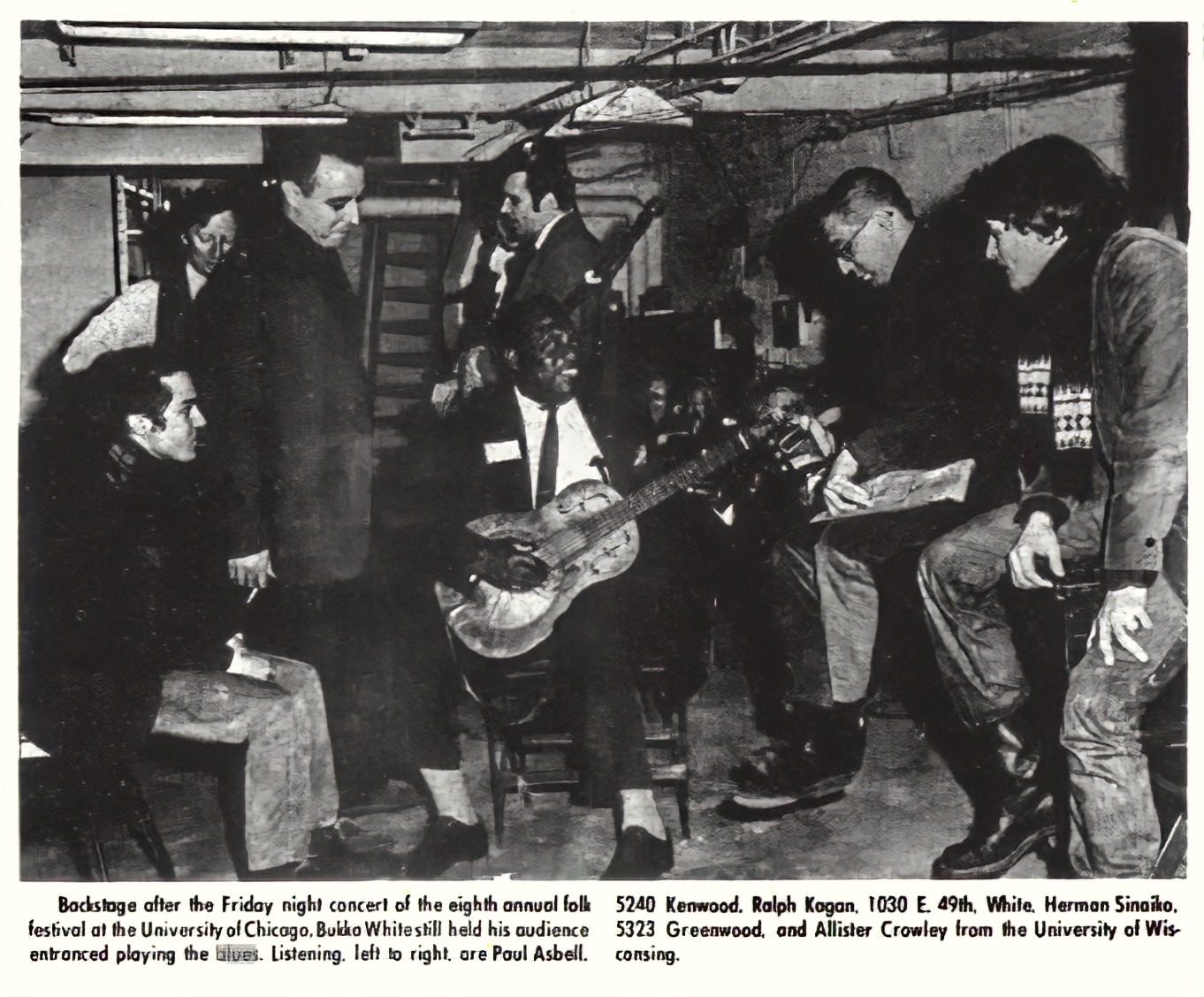

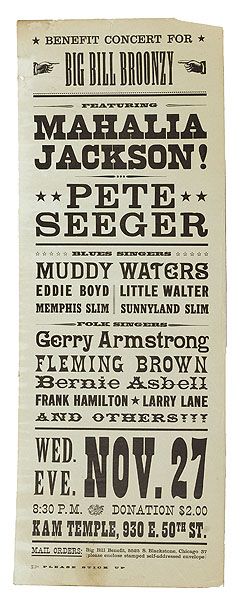

Those of us “of a certain age” will remember the experience of poring through cardboard boxes full of memorabilia relating to our parents, and finding a fascinating tidbit from their early life. Thanks to old friend Rik Palieri, I’ve just experienced the digital equivalent.

This poster, which I’m seeing now for the first time, is of an event that presumably took place in 1957, when I was 8 years old. The image ties together so many disparate pieces of my own life that my mind is racing as I reflect on all the connections.

The event itself was a benefit to offset blues singer and guitarist Bill Broonzy’s medical expenses, due to his ailing health. Bill was a friend of my parents, and I suspect my dad– in addition to performing on the program– may have been an organizer of the event, since the event’s location, KAM Temple, was around 2 blocks from our house on 50th St. (A few years later, after asking my mother why we didn’t go to temple like my cousins’ family, I briefly attended KAM myself. That short-lived experiment ended after a friend explained that the objective of attendance– something called a “Bar Mitzvah”– involved studying Hebrew in Sunday School for a year and half, and then receiving around $1500 in gifts. When it was pointed out that a substantial percentage of those gifts would be in the form of “Cedars of Lebanon” bonds, I decided that the numbers wouldn’t work for me, and left Sunday School soon after. But that’s another story, for another time…)

Many years later, in my teens, I became serious about learning to play the blues guitar styles I was listening to on recordings from the ‘30’s. By that time, I was beginning to realize that the Bill Broonzy who I was hearing perform virtuosic instrumentals and sophisticated studio session accompaniments– and singing racy, double-entendre “party blues”– was the same guy whose politically topical, down-home “folk-blues” I had heard around the house growing up. I also realized that, like many people, my mom had no idea of Bill’s earlier, racier musical career, and his subsequent re-invention– nor was she especially pleased by the notion. It was an early eye-opener for me about the complexities of the professional world… especially in the music biz.

The concert’s headliner, Mahalia Jackson, had by then been hailed as “the world’s greatest gospel singer”–a billing which implied that her name might actually be recognizable to mainstream popular culture in the US (and thus earning her the exclamation point!) A few months before this benefit concert, she had appeared at the Newport Jazz Festival, widening her exposure to white audiences. Her records had been in continual rotation in my parents’ home while growing up, and I remember seeing her sing in southside churches with my dad. Those early black church visits– and the awareness that the music itself was only a part of the total experience– have stayed with me all my life.